Top Sports News

LIV Golf Korea Prize Money Remains At $25M With Individual Winner Pocketing $4M Purse, Plus $5M Team Prize

The 2025 LIV Golf Korea prize money on offer this week is $25m, just like all 13 other LIV Golf events. Join us as well examine the full LIV Golf…

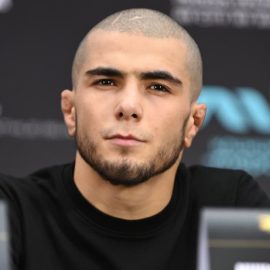

Teofimo Lopez Next Fight: ‘The Takeover’ Defends WBO World Super-Lightweight Title Vs Arnold Barboza Jr On May 2nd

The Teofimo Lopez next fight sees the WBO World Super-Lightweight Champion aim to defend his belt against the undefeated Arnold Barboza Jr in the main event at historic Times Square…

NFL

View allEagles star Saquon Barkley defends golfing with President Donald Trump after social media backlash

Philadelphia Eagles star Saquon Barkley has defended his decision to play golf with President Donald Trump amid considerable backlash across social media. Barkley, fresh off a career year where he…

ESPN’s Mel Kiper called the Cincinnati Bengals’ 2025 draft ‘ho-hum’

Over the weekend, the 2025 NFL draft happened in Green Bay, Wisconsin. It’s a time for teams to replenish their talent and build for the future. Each year, ESPN’s Mel…

NHL

View allHow To Watch Florida Panthers vs Tampa Bay Lightning: TV Channel, Live Stream and Preview For NHL Payoff Clash

The Florida Panthers host the Tampa Bay Lightning in Game Four of the NHL Playoffs, as the Panthers look to go 3-1 up and you can find out how to…

Montreal Canadiens Goalie Sam Montembeault Could Miss Game 4 Against Washington Capitals Through Injury

Sam Montembeault, the Montreal Canadiens No.1 goalie, could be set to miss Game 4 of the Eastern Conference Round 1 Stanley Cup Playoffs against the Washington Capitals. This comes after…

Research Features

View allWorst 21st Century Regular Season Records In The NFL: Will Anyone Go Winless In 2024?

With the 2024 NFL season just around the corner, we count down some of the worst records in the league since 2000 – with some memorably poor teams making the…

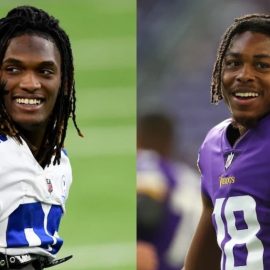

Top 10 Most Lucrative Wide Receiver Contracts Agreed Ahead Of The 2024 NFL Season

CeeDee Lamb landed one of the biggest non-quarterback deals in the NFL this week as he signed a four-year contract with Dallas – but where does the Cowboys star receiver…