Top Sports News

Exclusive: Panthers Legend Luke Kuechly Raves About Bryce Young, Talks No. 8 Pick

Carolina Panthers great Luke Kuechly believes we learned a lot about Bryce Young’s “makeup” and growth in his second season compared to his first. The No. 1 overall pick in…

Jordan Love Exclusive: Star Quarterback Explains How Packers Can Get To Next Level

Green Bay Packers quarterback Jordan Love is well aware that the team — including himself — needs to improve if they want to get to an elite level. The Packers…

NFL

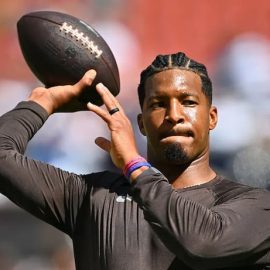

View allVeteran QB Jameis Winston signed a two-year, $8 million deal with the Giants

After his 2024 campaign with the Cleveland Browns, QB Jameis Winston was a free agent. The 31-year-old played in 12 games for the Browns last season. He went 2-5 in…

Texans’ Derek Stingley Jr. is now the NFL’s highest-paid CB at $30 million per season

In 2024, the Houston Texans won the AFC South and made the playoffs for a second straight season. Houston was 10-7 last year and beat the Chargers 32-12 in the…

NHL

View allColorado Avalanche General Manager Provides Update On Gabriel Landeskog’s Return From Injury

Colorado Avalanche General Manager (GM), Chris MacFarland, has given an update on the injury status of Gabriel Landeskog. Colorado Avalanche GM Gives Injury Update On Gabriel Landeskog The Colorado Avalanche…

Jessica Campbell and Emily Engel-Natzke Make History As First Female Coaches To Go Head-To-Head In NHL

Jessica Campbell and Emily Engel-Natzke have made history after becoming the first two female coaches to go head-to-head in the NHL. Jessica Campbell and Emily Engel-Natzke Make History In NHL…

Research Features

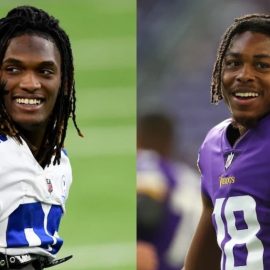

View allTop 10 Most Lucrative Wide Receiver Contracts Agreed Ahead Of The 2024 NFL Season

CeeDee Lamb landed one of the biggest non-quarterback deals in the NFL this week as he signed a four-year contract with Dallas – but where does the Cowboys star receiver…

Premier League Summer Transfers: Top 10 Most Expensive Signings So Far

The 2024/25 Premier League season is almost upon us and as English clubs prepare for the new campaign, we are counting down the top ten most expensive transfers so far….