In 1885, the Football Association announced to legalise the employment of professional footballers. Clubs could now pay their players a full working wage, quite in contrast to what had been the norm previously when teams were made up of amateurs.

Many clubs were enticed by the idea as it presented a lucrative opportunity to earn money; primarily from match day tickets, and immediately turned from amateur to professional. Blackburn Rovers, during the 1885-86 season, spent £615 on wages alone. The half-back James Forrest and the striker Joseph Lofthouse, both England internationals, were apparently on a whopping £1 per week. West Bromwich Albion paid its players 10 shillings a week but without any added incentives.

Nick Ross, Scottish defender and captain of Preston North End, had his salary increase to £10 a month when he transferred to Everton in 1888 – a very steep rise. If earlier records are to be believed, Ross’s wages were at least twice that of any player in the Football League.

In the next decade or so, other leading clubs like Newcastle United, Sunderland and Aston Villa paid their players a very good £5 a week. Football as a sport was getting more lucrative every year. But in 1893, Derby County requested the Football League to impose a maximum wage cap of £4 a week. Since most players also had other jobs besides their careers as footballers, and add to the fact that most did not earn as much as £4 in wages, the idea of a salary cap did not pose as a threat at that time. But many footballers at bigger clubs were on £10 a week who understandably, did not acquiesce with the proposal.

In the same year, the Football Association introduced the ‘Retain and Transfer system’ – an unfair and unjustified restriction that prohibited players from moving from one Football League club to another.

“In effect, the Football League abolished the free market where players’ wages and conditions were concerned… there were ‘escape routes’ to clubs and countries where a player could ply his trade freely and earn a reasonable (indeed, where some Southern League clubs were concerned, highly lucrative) wage…. Southern League clubs began enticing Football League stars to defect with promises of up to £100 signing-on fees,” writes John Harding in his book For the Good of the Game: Official History of the Professional Footballers Association.

So in 1898, after a meeting in Liverpool, the Association Footballers Union was formed, a precursor to today’s Professional Footballers’ Association.

Everton and Scotland internationals Jack Bell and John Cameron presided as the first chairman and the first secretary, respectively. The union had a total of 250 members that included some of the top names in English football of that era including Billy Meredith of Manchester City, Jack Devey of Aston Villa and James McNaught of Newton Heath among others.

But in 1901, the Football League imposed the wage cap and even abolished end of season bonuses which prompted the AFU to dissolve shortly afterwards after failing to achieve its objectives.

The following year, Welsh international and Manchester City full back Di Jones cut his knee on a shard of glass in a pre-season friendly. The wound festered and Jones died of blood poisoning and lockjaw. With no insurance in place and the game being a friendly, City did not accept the costs or liabilities as the said player was “not working”.

Jones’ City teammate Billy Meredith, now at Manchester United, along with other United players including Sandy Turnbull, Herbert Broomfield, Charlie Roberts, Herbert Burgess and Charlie Sagar decided to form a new Players’ Union. The first meeting was held on 2 December, 1907 at the Imperial Hotel in Manchester. Players from many other clubs attended including from City, Tottenham Hotspur, Newcastle United and West Bromwich Albion.

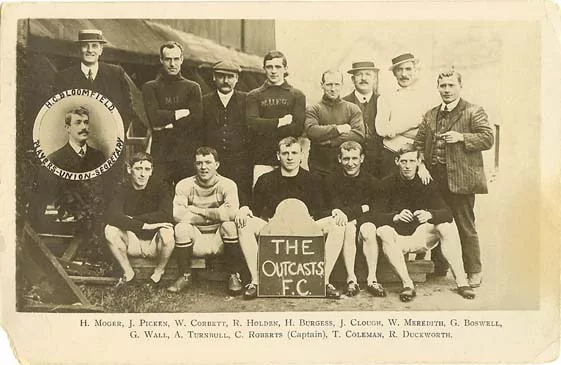

Meredith chaired the new Association of Football Players’ and Trainers’ Union and Bloomfield served as the secretary. The objective of the union was to force the FA and the League to abolish the wage caps. In 1909, the FA ordered the players to resign from AFPU and most did out of fear. But the whole team of Manchester United refused to back down and hence got suspended from their club. The press dubbed this team the ‘Outcasts FC’. Seventeen players from Sunderland did the same and refused to leave the AFPU. Tim Coleman of Everton, in what must have been a daring move, broke the ranks from his colleagues and rallied in support of these players. Gradually, the AFPU started gaining strength and forced the FA to officially recognise them and remove its sanctions on bonuses. The maximum wage cap however continued to hunt footballers until 1961.

At this point the maximum wage was £20 per week. The PFA, led by Fulham’s Jimmy Hill called for a strike on 21 January 1961. But three days before the planned strike, the FA caved in to their demands and finally abolished its maximum wage policy, nearly sixty years since its inception.

Cliff Lloyd, who served as the secretary at the PFA was the brains behind the legal proceedings and was involved throughout these negotiations with the FA.

One could argue if this victory gave rise to the concept of “player power” that is prevalent today.

Add Sportslens to your Google News Feed!