The diving side of the box is a pathway to many penalties some consider to be unnatural

While Darth Neydious might not have actually said that, it’s hard to refute the fact that diving is a crucial part of the modern game. Matches can be won or lost by dives (as was proven by Paul Pogba’s recent self-trip against Aston Villa), and no matter how many times the purists try to speak of the ‘spirit of the beautiful game’, they won’t be able to change that fact.

Under Law 12 of the FA’s Laws of the Game, it is stated that a player should be cautioned for ‘unsporting behaviour’. Unsporting behaviour includes ‘attempts to deceive the referee e.g. by feigning injury or pretending to have been fouled (simulation)’. Further, prior to the 2017/18 season, players could retrospectively be banned for ‘successful deception of a match official’, as the likes of Oumar Niasse, Manuel Lanzini and many others found out.

The second part went out of the window following the introduction of the Video Assistant Referee (VAR) in the 2019/20 season, as players could no longer deceive match officials, who had video footage readily available to aid their decision-making, or at least that was the plan. In the 2010s, an average of 25 bookings for simulation were handed out every season, but that number has dropped significantly post-VAR. Since March 8, 2020, only two such yellow cards have been brandished after over 200 matches of the Premier League.

This could mean one of two things – the presence of VAR has deterred players from diving to an extent that has nearly eradicated the offence, or referees are refraining from punishing divers, leaving such contentious calls to VAR. It’s hard to imagine the former since terms such as ‘diving fraud’ are still very regularly used on Twitter

I don’t but he’s levels above that diving fraud you rep

— Norville ‘Shaggy’ Rogers (@ShaggyRogers696) December 28, 2020

https://twitter.com/GeorgeWolves10/status/1343596006991130628

While the Bird app is prone to a lot of exaggeration, there is no refuting the fact that simulation continues to exist as a problem in modern football, although it does seem to have changed its shape post-VAR.

Back in the old days, players could quite literally kick the ground, take a tumble, and win a penalty. Take a look at this disgraceful piece of simulation from Jordi Alba, for example.

VAR may be much-maligned for many other things, but you have to concede that it has eliminated such terrible simulation altogether. There is no way anyone in the right mind would try to pull off anything remotely similar to that on a pitch where VAR’s cameras are menacingly monitoring your every step.

However, this is not to say that the entire concept of diving is extinct. Now, we have a different sort of simulation – a form which can even deceive an infinite number of cameras.

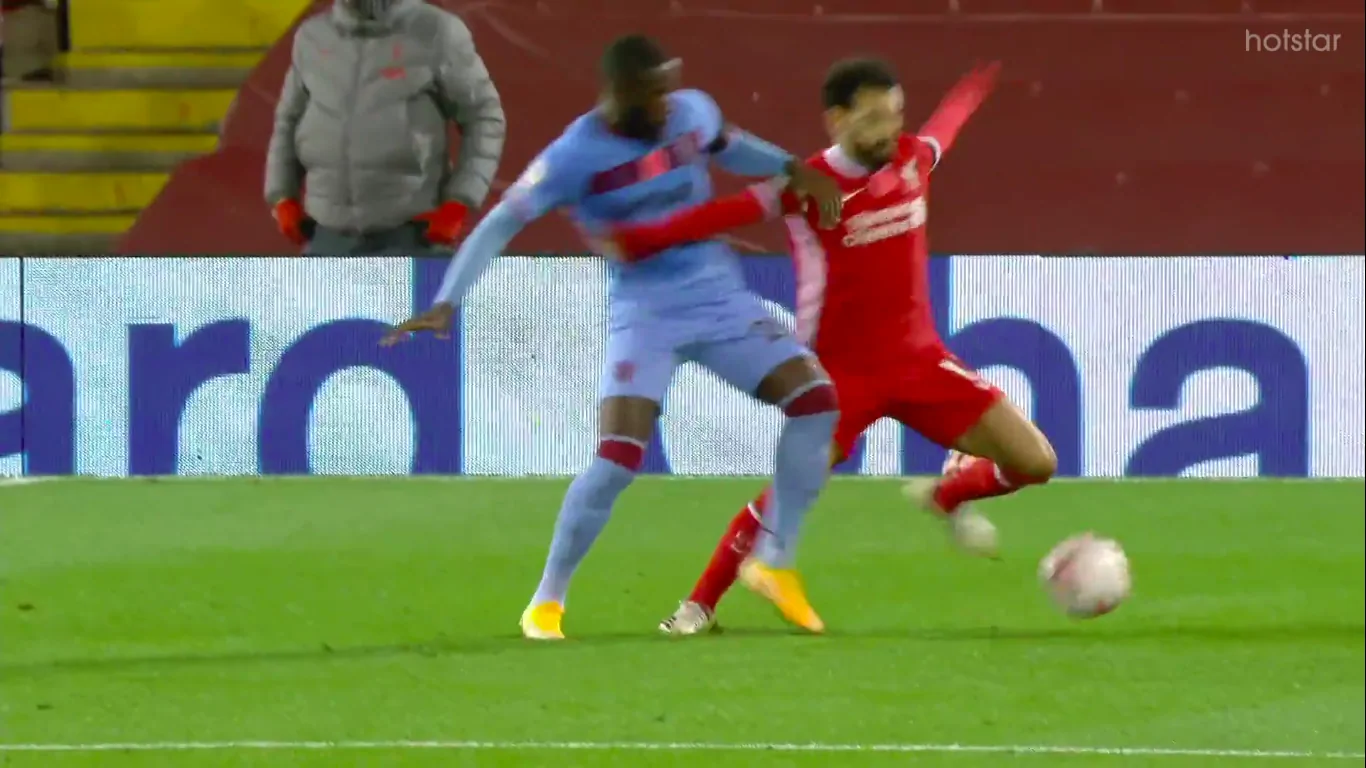

Here is an example of that new form of diving, which involves milking minimal contact. In the above image, Angelo Ogbonna’s left foot has ever-so-slightly nudged Mohamed Salah’s right heel, and the contact is undoubtedly not enough to cause the Egyptian to go down.

Here’s more proof of that – Salah quite literally places his right foot flat on the ground and lifts his other foot. Evidently, that contact was not enough to disrupt his balance, and the Liverpool forward could surely keep hold of the ball if he wanted to.

But, instead, he uses all of his strength to catapult himself to the floor, making the slightest of touches seem like an ankle-breaking challenge. The referee, Kevin Friend, was not in the best position, so he was deceived by Salah’s actions, and this is where VAR is supposed to come in. Now, anyone with two ounces of common sense would see that Salah was able to plant his foot after receiving that slight nudge from Ogbonna, meaning that his balance was not disrupted and that the West Ham defender had not committed a foul. However, VAR’s very special objective is to only intervene when there is a ‘clear and obvious error’, and that minimal contact is enough to sell the dive, especially when the footage is replayed in slow-motion.

So, Salah got away with a penalty for an irrefutable dive, deceiving both the referee on the pitch and the VAR official, while also avoiding any retrospective action.

If this was a one-off, it might have been overlooked, but sadly, it was not.

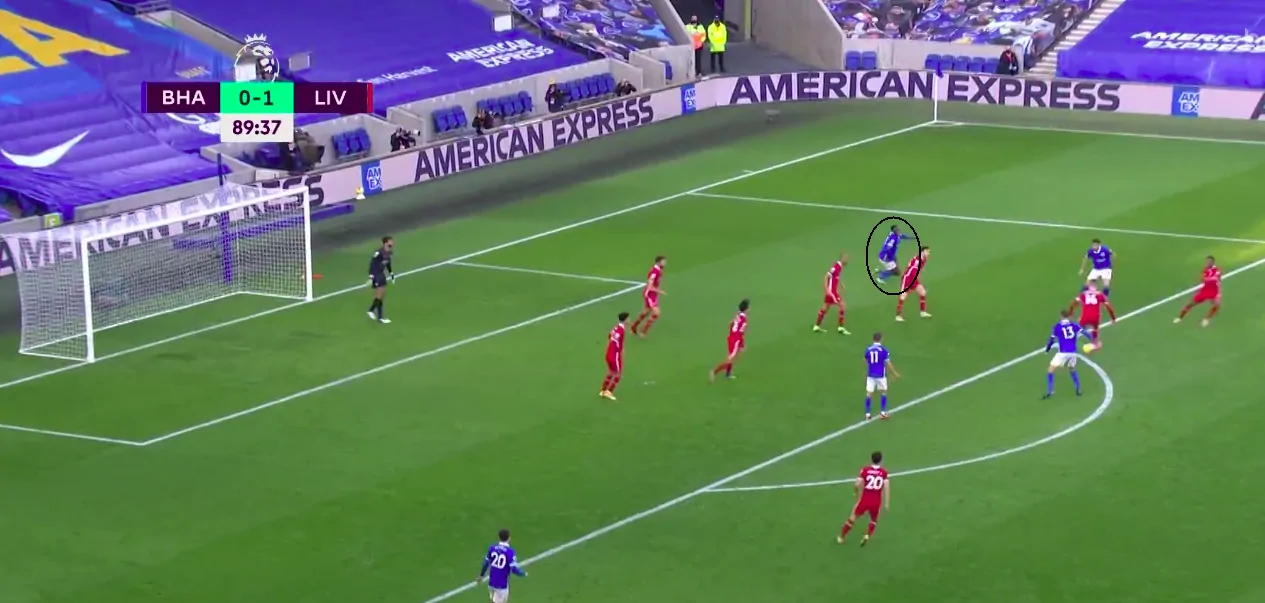

The second example we’ll be looking at went against Liverpool, as an equal clash of nothing more than toes between Andy Robertson and Danny Welbeck caused the latter to go down.

Yet again, Welbeck didn’t lose his balance and was able to plant his foot firmly on the ground while taking the other off it, but he saw that the ball had gone far away from him.

His desperation to win a penalty led him to go down in a heap after taking two more steps, but the referee bought it once again. The minimal contact meant that VAR had no grounds to overturn the decision despite the fact that Welbeck was able to take three steps without any issues after suffering that massive amount of contact.

In both cases, the referee was deceived, and in both cases, VAR failed to overturn the decision. So, the problem lies in one of the two areas – the referee’s decision-making or VAR. There is no question that match officials make mistakes, in fact, that fact is the very basis to justify the use of VAR, so the problem clearly lies in the latter.

However, VAR has worked perfectly fine in almost all other countries it has been used. Think about it, when was the last time you heard of massive uproar against VAR in the Bundesliga, La Liga, Serie A, or even in UEFA competitions. Perhaps, the problem lies not in VAR, but in the implementation of it in England.

For example, here are the VAR rules applied in Germany, as stated on the official Bundesliga website:

There are four clear cases in which a VAR can review incidents via TV replays.

Goals

-

- Was a goal wrongly ruled out for offside or given when a player was offside? Was a foul committed or some other rule breached in the scoring of a goal?

Red cards

-

- Is the sending-off justified? Has any unsporting conduct occurred behind the referee’s back or off the ball?

Penalty

-

- Is the decision to award the spot-kick correct? Should one have been given for a foul not spotted by the match referee?

Yellow/red cards

- Is there a case of mistaken identity?

Who has the final say?

The VAR can only give their opinion. The match referee has three options when they hear what their colleague has to say:

- leave their decision unchanged; accept the VAR’s suggestion regarding a decision; watch the incident again themselves via a TV screen inside the stadium.

In contrast, here are the VAR Rules applied in the Premier League, as stated on its official website.

The 2019/20 Premier League season was the first to feature the Video Assistant Referee (VAR) after the clubs voted unanimously in November 2018 to introduce the system.

All 380 Premier League fixtures in a season will have a VAR, who is constantly monitoring the match but will be used only for “clear and obvious errors” or “serious missed incidents” in four match-changing situations:

Goals

Penalty decisions

Direct red card incidents

Mistaken identity

The final decision will always be taken by the on-field referee.

VAR will not achieve 100 per cent accuracy, but will positively influence decision-making and lead to more correct, and fairer, judgments.

In the Premier League, there will be a high bar for VAR intervention on subjective decisions to maintain the pace and intensity of the matches.

Factual decisions, such as offside or if a foul was committed inside or outside the penalty area, will not be subject to the “clear and obvious error” test.

Spot the difference? “Clear and obvious error”

The Video Assistant Referee, as the title suggests, is supposed to assist the referee in making the right decision, but not go about making decisions for him. The “clear and obvious error” rule means that Premier League referees never get to have a second look at contentious calls where multiple angles would help. Instead, their decisions are only scrutinised when they are quite blatantly wrong, and this means that cases such as the ones discussed above are invisible to VAR’s radar.

Here’s another example of a case which would have been reviewed in a place like Germany, but it wasn’t in the Premier League:

This angle from across the pitch showed that it was Schlupp who backed into Lamptey and then threw himself to the ground, as is proved by the fact that he had both feet in the air before hitting the grass:

This clearly indicates that Schlupp forced himself down and was not disturbed by Lamptey’s hand. If he was actually pulled down, he would have quite simply fallen back and not jumped with both feet in the air. However. for VAR, this was not a “clear and obvious error” due to the hand on the shoulder, so the referee didn’t get a chance to review it. If we didn’t have the clear and obvious error rule, there is a good chance that the referee would have come to the pitchside monitor, seen this second angle and perhaps changed his mind.

The issue certainly lies in the “clear and obvious error” bit, because that is the only difference between VAR in England and elsewhere, and as aforementioned, nobody else seems to be having such a big problem. This season, the FA tried to make things better by finally introducing the pitchside monitor, but it hasn’t worked – referees have stuck to their onfield decision after taking a look at the footage themselves only twice so far this season, which is too low to be right.

It’s easy to blame VAR for ‘ruining the game’, but it’s surprising how almost nobody has noticed that the game has only been ruined in England, not anywhere else. As is the case with almost any other piece of technology, the problem lies not in VAR, but in its implementation.

As far as diving is concerned, no amount of technology will be able to eradicate that dark phenomenon from the beautiful game. While we can certainly reduce the number of occasions when a dive goes unpunished, it is ultimately up to the players to stop trying it, and until simulation continues to offer rewards such as cheap penalties, it’s impossible to imagine every single footballer refraining from trying to buy some free spot-kicks.

Add Sportslens to your Google News Feed!