Football is a passionate game. That is like saying cliff-walking is a dangerous one. Plenty of sports have their passion, but to me, football’s remains the most tribalistic. How many people do you know who can transform from run-of-the-mill Mr. Average to vein-through-the-head Mr. Angry, and all because of a contentious penalty decision. The game brings to the surface emotions that don’t usually appear in everyday life, the anger, the venom, the vitriol, the bitterness, the greed, the elation, the relief. They are all extremities too. If a ref disallows a perfectly good goal, it’s as if he has burgled your shed. If your side secures a late winner, you act like it’s the birth of your first child. All conventional logic goes out the window when football is involved. It’s a primal game.

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, it is also a game which has an undeniable link to violence. When emotion and passion runs so close to the surface, and when people devote so much of their time to their chosen hobby, it is pretty obvious that somewhere along the line, lines will be crossed.

In England, football hooliganism has been a major talking point since the 1970s. In the 1980s it reached new levels of hysteria, with the Prime Minister wading into a debate over Identity Cards for fans, and Ken Bates calling for electrified fences to pen in the “animals”. The Heysel stadium disaster of 1985 led to some serious questions being asked of this “plague” on football. English clubs were banned from Europe for five years, and told to clean up their act. Still the problems persisted. A lot of people claim that the “feel-good factor” which returned to English football following successful campaigns at Italia 90 and Euro 96 has led to the emergence of a new, more laid-back fan, but cynics (or realists) claim that violence at football is still very much an issue, it is just reported less as it tends to happen well away from the stadiums themselves.

This is a topical issue at the moment in England. A few week-ends ago during the FA Cup clash between Hull City & Millwall at the KC Stadium, trouble emerged in the stands amongst the visiting supporters. Seats were ripped up, toilets and refreshment stalls were destroyed, and twelve arrests were made, with many more anticipated once police study CCTV footage from the stadium. It was a nasty reminder that whilst policing at English football grounds is undoubtedly more efficient these days, the under-current of “trouble” still lurks close by.

It is hard to pinpoint exactly when the culture of football violence began to emerge into English football. As far back as the 1880s and 90s, gangs of football supporters termed as “roughs” are thought to have caused trouble, usually at local derby matches. Understandable really given that transport restrictions made travelling to away games pretty much a no-go area. In 1885, one of the first ever reported instances of football violence came when Preston North End’s “Invincibles” team defeated Aston Villa in a friendly match. After the game, both sides were pelted with stones, sticks and fists as they left the pitch. It was pointless, purposeless, and brainless. Three words that have become almost synonymous with the concept of the football hooliganism.

The Football Special. Three words that resonate with any English football fan over the age of 30 I’m sure. Basically, the Football Special was a chartered train service which was used specifically to transport away fans to football matches. The idea of the Football Special was to keep football fans away from ordinary travellers, minimising the risk to the general public, as well as ensuring that police at the away ground would be aware where and when the visiting fans would be arriving. The trains usually consisted of redundant stock and spare carriages, and as such were very minimal. Most fans’ memories of Football Specials consist of being herded like cattle, and treated like animals. Bars across the windows penned fans in, and with no toilets on board (but alcohol on sale), conditions were always going to be pretty grubby to say the least.

If the 1960s sowed the seeds for football hooliganism, the 1970s saw the “firms” make it into the big-time, with barely a weekend passing without graphic images of terrace fighting. At the 1974 UEFA Cup final between Feyenoord & Tottenham, scores of Spurs fans ripped seats and threw them at police and home supporters, before rampaging through the streets of Rotterdam. Their legendary manager Bill Nicholson was believed to be deeply affected by this growing culture in football, and the Rotterdam violence was cited as a major factor in his decision to walk out of White Hart Lane a few months later. The following year at the European Cup final in Paris, Leeds United fans responded to some questionable refereeing decisions by raining down missiles on the pitch and destroying cars and businesses outside.

It isn’t rocket science I suppose. Put someone who goes to football and wears casual designer clothes together, and you have the Football Casual. The origins of the Football Casual are said to come from English clubs’ first forays abroad, and the looting that would go on amongst their travelling support. My own club Liverpool earned a huge reputation for bringing back the latest designer clothes and trainers from their many European trips, and soon a competition was underway amongst the main firms to wear the best designer gear, listen to the best music and, of course, cause the most trouble. Gone were bovver boots, team colours and snorkel parkas, in were wedge haircuts, adidas trainers and designer jeans. The fashion culture also meant that the number of fans involved would bulge, with the new casuals jumping on the bandwagon, looking for a bit of action, rather than just the hardcore minority.

So, if the 1960s was the start, the 1970s was the adolescence, the 1980s was undoubtedly the nadir for football violence. In stadiums at least. And 1985 was undoubtedly the lowest year of all. In March of that year, BBC viewers were left open-mouthed as an FA Cup Quarter Final between Luton Town & Millwall at Kenilworth Road descended into what most writers described as “the worst example of football violence seen at an English ground”. Visiting Millwall fans, enjoying the fear that their media-enhanced reputation had given to them, simply tore Kenilworth Road apart. Ripping scores of vivid orange plastic seats up to use as weapons and shields, Millwall fans charged onto the pitch, fighting with police and opposition fans. The game was halted twice, and at the final whistle, the pitch was invaded again, with several injuries ensuing. And all played out on live television.

Outside the ground, pitched battles were fought between The Bushwhackers, and Luton’s own MIG crew, with police in the middle. Following this most public of reminders of the perils of hooliganism, the British Government, led by PM Margaret Thatcher, called for serious measures to be put in place to combat fan violence. Thatcher demanded “stiff prison sentences” for those found guilty of stadium violence, whilst Chelsea chairman Ken Bates, never one to shy away from an inflammatory soundbyte, claimed he wanted to erect electrified fences at Stamford Bridge in order to keep potential troublemakers in check. The Government proposed an idea to introduce ID cards for football fans, in order to monitor exactly who was travelling to matches, but this idea never got off the ground.

The following month, a game between Birmingham & Leeds at St Andrews ended in tragedy when a 14 year-old boy was crushed to death beneath a wall which had collapsed outside the stadium following a day of violence described in one investigation as “more like Agincourt than a football match”. Leeds fans set fire to stalls in the away end, threw concrete breezeblocks at opposition fans and tore up seats. Even Leeds boss, an Elland Road legend, Eddie Gray, was targeted with missiles as he pleaded in vain for the fans to stop their rampaging.

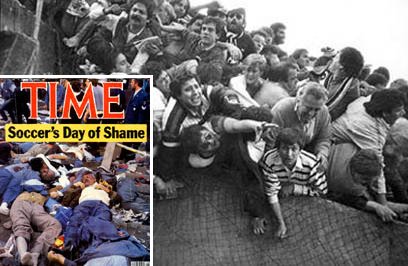

Of course the details of that fateful May night are a sensitive subject, and no one truly knows the spark for the mayhem (if there even was one). What we do know is that Liverpool & Juventus fans ended up confined together in a so-called “neutral area” (tickets distributed to local fans were always likely to end up in the wrong hands), and violence ensued. As Liverpool fans charged their rivals, the Juventus fans fled to the safety of their own end. But under weight of numbers, a wall separating the Juventus end from the neutral area buckled and collapsed, killing 39 supporters. Battle continued, despite the fatalities, and the game was held up, with the captains of both sides- Phil Neal & Gaetano Scirea- appealing for calm from the supporters. The game was eventually played, but under a black cloud, Juventus’ 1-0 win paling into virtual insignificance.

In the aftermath of Heysel, English clubs were banned from Europe for five years (Liverpool for six), as the FA looked to clean up its national game’s reputation. The Hillsborough tragedy of April 15th 1989, where 96 Liverpool supporters were killed in a crush at their side’s FA Cup Semi Final with Nottingham Forest, led to the Taylor Report, which recommended that all major football stadia reverts to the all-seater mode, minus the perimeter fences which had proved so dangerous. This, coupled with improved policing and stewarding at grounds, has led to a decline in the number of arrests made at football grounds since 1990.

That’s not to say that football violence at stadiums does not happen any more. In February 1995, England fans rioted at a friendly with the Republic of Ireland in Dublin, causing the game to be abandoned. 50 people were injured. In 1997, during England’s critical World Cup qualifier with Italy in Rome, fans clashed on the terraces with Italian police, who steamed in with batons. In the same stadium in 2007, Manchester United fans clashed with police on the terraces in similar fashion, whilst Spurs fans were seen scrapping with Spanish police during their UEFA Cup tie with Sevilla that same week.

The media coverage that these incidents, as well as the Hull/Millwall one last month, expressed shock that this kind of thing still occurs in the English game. Police acted quickly to identify those involved, and clubs have a far stricter policy for fans caught offending these days. Police are encouraged not to wade in with batons flailing, as is often the case on the continent, but to examine CCTV footage and identify suspects, with banning orders and prison sentences dished out. The media also plays its part, publishing photographs of suspected hooligans, whilst the BBC television programme “MacIntyre undercover” saw undercover reporter Donal MacIntrye’s investigation into Chelsea football hooligans lead to a series of arrests, with several of Chelsea’s notorious Head-Hunter crew jailed.

Of course the increased publicity and scrutiny given to football violence since the rarely reported days of the 1960s has had an effect in terms of violence within the stadiums, but many experts believe that whilst violence at matches in England is undoubtedly on the fall, organised gangs still operate regularly away from the CCTV-stained grounds. Indeed, in 1985 five fans were stabbed on a cross-channel ferry to France after a three-way fight involving fans of West Ham, Manchester Utd & Everton, whilst in March 1998 a Fulham fan was kicked to death outside Gillingham’s Priestfield Stadium when fighting broke out in a nearby alleyway.

However these incidents, whilst tragic and unacceptable, are a lot fewer and further between than in the Hooligan Heyday of the 1970s and 80s, when it seemed that every weekend there were new tales of woe from clubs, fans, police and players. It will probably never be stamped out, in any society there will be an element of idiocy and violence will always follow football, as long as the game remains as fiercely passionate as it is. They say the money in the game is driving out “old-school/real fans”… what I say is: if those fans are anything like this lot, then… good.

.

Ten Worst Football Riots

.

|

Millwall vs. Luton — 1985 |

| The most memorable (for the wrong reasons) FA Cup quarter final of all time. Fans clash before, during and after the game, tearing up seats and fighting with police. . . |

| Rangers vs. Zenit St. Petersburg — 2008 |  |

| The 2008 UEFA Cup final, held at Manchester City’s Eastlands Stadium, was memorable for Zenit St Petersburg’s impressive win. But also for the behaviour of a number of Rangers fans outside the stadium. Trouble brewed as drunk fans rioted in the centre of Manchester, clashing with police and trashing cars and shops. |

|

Sparta Prague vs. Dinamo Zagreb — 2008 |

| A UEFA Cup tie between Czech side Sparta, and Croatian outfit Dinamo, descended into mayhem. 150 Croat supporters were detained as they rioted with police and home fans in the centre of Prague. . |

| Dinamo Zagreb vs. Red Star Belgrade — 1990 |  |

| “The match that started a war” according to some experts. Red Star’s “Delije” & Dinamo’s “Bad Blue Boys” clashed at Zagreb’s Maksimir stadium in 1990. This riot is famous for Dinamo’s 21 year old captain Zvonimir Boban, who reacted to seeing one of his side’s fans being beaten by a police officer by launching a roundhouse kick to free the fan. Madness. |

|

Danubio vs. Nacional — 2008 |

| The riot that stopped a season. Nuff said. . . . . |

| Liverpool vs. Juventus — 1985 |  |

| The most high profile on our list, due to it’s significance, and the tragedy involved. 39 Juventus supporters were killed when a wall collapsed at Brussels’ Heysel Stadium ahead of the 1985 European Cup final. RIP. |

|

Catania vs. Palermo — 2007 |

| The Sicilian derby proved to be fatal, as 40 year old police officer Filippo Raciti was killed after a homemade bomb was thrown into his patrol car as rival fans of Catania & Palermo clashed before, during and after their side’s meeting in February 2007. Serie A football was suspended for three weeks as a consequence. |

| Wroclaw — 2003 |  |

| Poland is a country plagued by football hooliganism, in 2003 the city of Wroclaw was the setting for an organised brawl between fans from Wroclaw, Poznan, Krakow, Gdynia & Lubin. One person died, whilst 229 were arrested. |

|

FC Zurich vs. Grasshoppers — 2006 |

| Switzerland is another country with football violence issues, here we see why the Zurich/Grasshoppers derby is not known as the friendly derby any longer. |

| Birmingham vs. Leeds — 1985 |  |

| 1985 was when football reached its lowest point in England. Not so much the standard of play, but the behaviour of its fans. At this second division game, Leeds & Birmingham clashed before, during and after the match, ripping St Andrews apart, and killing a fourteen year old fan when a wall collapsed on top of him. When analysing football’s problems, Lord Justice Popplewell described the scenes as “more like Agincourt than a football match” |

Also See:

20 Most Bizarre Incidents Ever in Football

Top 15 Craziest Red/Yellow Cards

10 Crazy Fans Who Shook The Footballing World

Add Sportslens to your Google News Feed!