Thursday was the five-month anniversary of Jürgen Klinsmann’s appointment as head coach of the United States men’s national team. In that short time, he has presided over seven games and has a paltry 2-1-4 record.

He has also instituted some controversial player-selection policies, in some instances preferring European-born players to Americans. This has led to some backlash, most recently this morning from U.S.-born professional player Preston Zimmerman that started some discussion on Twitter about Klinsmann’s policies:

On Nov. 10, Brian Straus of Sporting News published an interview with Klinsmann ahead of the 1-0 U.S. loss in France. In it, Klinsmann made some assertions that implied the U.S. is better off with Europeans on its national team than Americans.

For example:

“It’s a different part of American culture. It’s the global picture that America represents. Those are kids who came through military families or for whatever reasons, working reasons of their parents, then they grow up with a different educational system, which gives them in soccer terms an edge ahead of American kids growing up in the U.S. They go through thousands more hours of playing the game than the American kid because the American kid only plays organized [soccer]. They come through different systems that gave them, especially, a technical advantage, an advantage in terms of how they read the game, anticipate the game, because the more you play the more you read things ahead.”

But the fact that he’s selecting foreign players is not his fault; it’s society’s:

“Now you live in this dual-citizenship world that is normal. It’s globalization. It’s just the way it is.”

Klinsmann obviously has a disdain for the grassroots of the American soccer system. He doesn’t seem to understand that it is different here; the same things that work in Europe or South Americ will not work in the U.S. The landscape is changing toward a more hybrid system with European allusions, but it will never be exactly the same.

The U.S. Soccer Development Academy is expanding, with Major League Soccer clubs taking a greater interest in youth soccer than ever before. However, most of these players will continue to go to college than straight to the pro ranks when they turn 18. The very top players who are ready for it will make the jump to the first team; others will get four more years (some less, if they leave early) to develop as players before taking that leap.

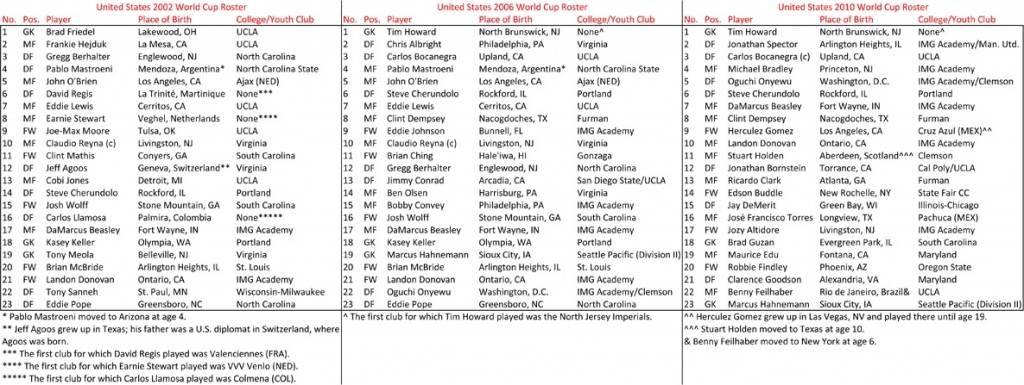

Looking at the last three U.S. World Cup rosters, the American system has fared just fine. Just six players out of 49 grew up in what could be considered a non-American system (youth play outside of the country):

These American-born players made their mark on the college system before becoming professionals, and they made it to the quarterfinals in 2002 and won their group — which included England, a nation that exemplifies the club youth academy system — in 2010.

Evidently, being a non-American does not necessarily make a player better.

Those 2002, 2006 and 2010 players who did not play in college played for the IMG Academy in Bradenton, Fla., which is the precursor to and a model for the current U.S. Development Academy system. IMG still has two teams participating in the new system, but graduates of the old academy include Landon Donovan, Damarcus Beasley, Michael Bradley and Jozy Altidore.

The academy system developed from that early start, and now all clubs under the Development Academy umbrella receive support from the U.S. Soccer Federation, not just IMG. To continue finding quality youth players, this system has to keep developing.

It’s off to a fine start — most NCAA Division I recruits played at an academy, and 16 of the 20 members of the U-17 national team that just won the 2011 Nike International Friendlies play for an academy side.

Additionally, Klinsmann has to realize the right balance between the European system and the existing American system. Imposing too much change will destroy all the work that has been done up to this point to find a system that is uniquely American but still effective on the global soccer stage.

Finally, a few more MLS selections to U.S. friendly squads would be nice, instead of European-born and -based players of whom nobody has heard or seen play.

Hopefully, the U.S. will be holding the World Cup in 2014, and Klinsmann will look like a genius despite his rocky first few months in charge. But that’s a far cry from the current look of things. If World Cup qualifying starts slowly for the U.S., changes have to be made quickly.

Sacrificing this World Cup cycle for future cycles would be unacceptable because the talent the U.S. has right now demands that success be immediate, not sometime in the future.

Liviu Bird is a goalkeeper for Seattle Pacific University and editor-in-chief of The Falcon, Seattle Pacific’s student newspaper. Follow him on Twitter.

Add Sportslens to your Google News Feed!