Fan’s are big lovers of at least having a striker on the pitch, funnily enough. Scotland’s defeat to the Czech Republic will possibly go down as Craig Levein’s defining moment if things don’t go so well, his 4-6-0 formation failing to keep the Czechs out and failing also to provide much attacking threat in return. It’s definitely understandable to be annoyed if you are a Scotland fan to see the tartan army’s chosen do the equivalent of tie their hands behind their collective backs.

So perhaps it was at least some consolation for your average Scotsman to see a striker at least in the defeat to Brazil, even if a fan did inadvertently bring controversy upon the ninety minutes. Consolation in the face of the fact that the co-commentator’s thought that ‘Scotland would be pleased to lose only 2-0’ sums up Scotland’s plight. Simply they were outplayed, as most people could have predicted. They barely found an attacking threat where Brazil could have easily scored more then they eventually did, a scenario all too familiar to the smaller teams in qualifiers – big international teams turn up, keep the ball for 85 minutes of the game, win by two or three goals. Despair for Scotland, who are as far away from qualifying for any big tournament as they ever have been.

But, there might be hope for small teams of the future, if their coaches are willing to experiment.

Ferguson’s example.

Step back to January 31st 2010, when Arsenal were struck out of the title race by Manchester United, in part by the key role of false nine striker Wayne Rooney. To quote the BBC report of the Gunner’s 3-1 loss. ‘Sir Alex Ferguson’s champions unleashed a devastating display of sweeping, counter-attacking football inspired by the brilliance of Wayne Rooney and Nani.’

Which says a lot more then simply those twenty two words. Firstly that United played on the counter attack, possibly acknowledging that Arsenal could play the ball better then United. Certainly, despite United edging the possession stats, (52 % to 48% in Man United’s favour) Arsenal had more shots on and off target, more corners and United committed more fouls.

And in any case it’s fair to suggest that Arsenal can outplay any team in the premier league, so a recent trend of United and Chelsea is to hit them on the counterattack, and United in particular on this occasion used Rooney dropping off deep into midfield and taking a defender with him, leaving Arsenal to cope with United’s two very, very aggressive wingers moving lightning fast into the bigger gaps left by a central defenders departure. The result being that Nani, Park and Rooney feeding off a Nani return crushed Arsenal beneath their clinical goals.

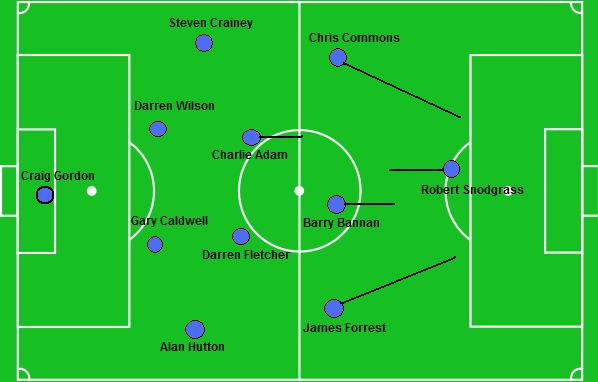

Zonal Marking talks about this game as ‘the probable death of Arsenal’s title hopes’ and further on moves on to say the game could well also be ‘the death of the traditional striker at top clubs. But why not smaller teams? They after all, are constantly in danger of being outplayed by the bigger teams, even more so with Barcelona’s tika taka tactics coming into fashion. But with the addition of a false nine, clubs that would usually be under the cosh can spring a surprise. Like Scotland. Take, for example, the experimental line up below.

Kicking your opponent in the behind.

Now immediately upon posting that picture in the article I can imagine the groans of ‘not again, dear sweet William Wallace…’ from Scottish fans seeing that the front player does in fact drop into midfield in this idea, but give me a chance to explain, and bear this in mind; our front three in this formation are very, very important.

Take for example, Robert Snodgrass. He is going to be our ‘false nine’ in this little experiment. He is going to drop off the defenders and pull them all over the place. But that isn’t the only thing a false nine does. The more important problem a false nine player poses is simple in the fact that opponents have a big dilemma in dealing with it.

For example, a defender can tight mark our false nine, that is if they want to have their defensive line made all the more fragile by said false nine dropping deep, and giving the wingers reign to stream into the gaps left, like Zonalmarking talks about in the above analysis of that so important Arsenal game.

Of course the defender can choose not to go with the striker, which leaves the defence a little more secure. On the other hand, then the false nine does something even worse. It helps in the overwhelming of that midfield which so used to simply making a little team chase shadows are now suddenly outnumbered in midfield.

The spare man.

So here we have a demonstration of how it could have worked against Brazil. (Assuming that Fletcher had in fact been there) Lucas against Bannan, Elano against Adam and Ramires against Fletcher, all making different interesting runs to try and outfox the opposition. But it is going to be Snodgrass making a key difference here. By dropping into free space and no defender going with him Snodgrass hands a key advantage to the Scottish midfield, that being a free man in space. Suddenly, Brazil’s midfield are in trouble – Snodgrass can get in between the midfield and defence and with the support of midfielders like Adam, Bannan, Forrest and Commons, can begin to hurt Brazil’s defence.

Of course Brazil could pull Alves further inside to keep tabs on him, or pull Jadson back to keep tabs on him, at the same time either limiting the threat from a world class fullback and leaving Commons free on the wing, or in pulling Jadson back negate a wing threat and leave Crainey free to overload Alves. If Snodgrass were to move into space on the other side of the pitch, the same result occurs. Brazil can’t win, in the sense of that small battle at least.

Big team troubles.

Of course its easy to argue that Brazil could do the same thing. As in draw a striker back and help his team mates in that three on four battle in midfield. And arguably Brazil could certainly find a striker capable of running between the lines, holding the ball up and supplying creativity. But in doing so, Brazil remove an outlet from the attack – suddenly Brazil have less of an outlet in attack, him picking up Fletcher while the rest of the midfield rearrange to pick up other players.

In effect they would be reacting to Scotland’s game rather then the other way around and imposing their star players on Scotland, who would have in effect not just largely curtailed a front player, but Brazil’s central front player, which would serve Scotland well in keeping Brazil out. Certainly, the false nine has the possibility of making the game more uncomfortable for more illustrious opponents.

The problem of experimenting.

That said it wouldn’t just be the Brazillians with a bit of a puzzler on their hands. It is only really Roma and Manchester United who have previously implemented false nine based strategies in the past on a regular basis, suggesting the sheer difficulty in the execution. Scotland do not have a Wayne Rooney to lead the line, and they do not have a Francesco Totti. Their main striker is a speedy but ultimately, blunt striker in Kenny Miller who led the line for the worst ever team in the premier league. This is in fact where Snodgrass comes in as very much an experiment. He has skill and creativity, and good technique. A goalscoring striker he is not, but perhaps, just maybe, he could fill the role that Scotland would need him to perform.

In midfield though, Scotland do have the creativity they would need. They have a champions league midfielder in Fletcher and several creative midfielders who can support Snodgrass in his role. They have up and coming players in defence, like the ball playing Danny Wilson, advanced playmakers like Barry Bannan and the very, very direct young winger James Forrest. In other words, they have a midfield that can create and assist in the attack. And therefore, perhaps they and other teams can look to what is essentially a 4-6-0 formation to give bigger sides with everything their way cause for concern.

Add Sportslens to your Google News Feed!