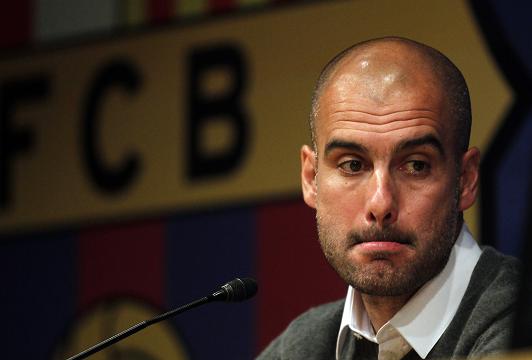

His expression said it all. You’d think the man who coached Messi to four Ballon d’Ors, during his tutelage at the club, would’ve seen all the skills and tricks of the Argentine maestro by now. But Guardiola’s need to hide his face in exacerbation would suggest otherwise.

On Wednesday evening though, Pep Guardiola will make an official return to the Camp Nou. This time, neither as a fan nor a coach, but as an enemy. And should he decide to take a seat in the one of the most iconic venues in world football, it will be on the opposing bench as Bayern Munich’s manager.

With speculation rife about his future in Bavaria, the 44-year-old tactician will hope that his boyhood club will lose, not that it will be an easy job.

Indeed, while Guardiola has the tactical nous to, indeed, out-wit his opposite number, the comparatively inexperienced Luis Enrique, with an injury-ravaged side and perhaps keep the Messi, Neymar and Suarez attacking trident at bay, the pressure of proving a point in front of the fans who, not too long ago, hailed him as a deity, might just get to him.

Upon results of the semi-final draw, Barcelona president Josep Maria Bartomeu remarked: “I hope and expect there to be a great welcome for Guardiola – he will be handed the honour that he deserves,”

Fittingly, the man who was at the centre of Johan Cruyff’s ‘Dream Team’ success during the 80s and 90s would eventually return to the club, not only to revitalise ‘total football’, but to improve on it. Under Guardiola, Barcelona played a high-intensity, possession based style of attacking football which utilised technically proficient players to slowly chip away at the opponents with quick, short passing. While the spotlight was often placed upon Barcelona’s abilities in the final third, not enough recognition was given to the fact that Guardiola had managed to build one of the best defensive structures of the generation.

The success of the team was inevitable, 14 titles in four years including two European Championships, three La Liga titles and two Copa Del Reys saw him obtain legendary status at the club. Citing fatigue, his departure angered several sections of the media as well as numerous supporters at the time. Still, given his contribution, it was virtually impossible to not allow Guardiola to leave the club for a sabbatical. But his departure didn’t leave the club in good stead. Far from it.

Barcelona is a club shrouded richly in tradition, identity, philosophy, and politics. It was former president Joan Laporta who saw the potential in Guardiola as the club’s first-team coach. The same man who convinced the young manager that he was the ideal successor of Frank Rijkaard. Laporta was the man who was a friend of Cruyff, who shared the same vision and philosophy as the Dutchman and the man who had given the legendary player turned coach the title of honorary president. If anything, Cruyff was seen as the precursor to Guardiola and Laporta saw the similarities between the pair.

Yet, by the time Guardiola had departed, Barcelona, politically, were in turmoil. Gone was Laporta, and in came his nemesis Sandro Rosell, who eventually summoned Cruyff to hand in his honorary presidency. It was a sign that the now former president and his assistant, now president, Josep Maria Bartomeu, would retaliate and evolve Barcelona into an institution which could do away with their history, identity and philosophy. If anything, the pair was at the forefront political movements, not just in and around the club, but in secular society itself, something which caused deep divisions between Guardiola and the board. While they sought to make Barcelona literally ‘mes que un club’, they, ironically, made it ”less’ que un club’.

In addition, Guardiola saw the media as Rosell’s puppet, and gave the public a wrong perception of the coach. Even after Pep’s eventual departure, the media failed to leave Guardiola alone, at first saying that the former coach believed Vilanova wouldn’t be able to control the group of egos, that is, after countless reassurances from Guardiola himself that Tito was well suited to the role. Even during Vilanova’s rehabilitation in New York, when Guardiola allegedly didn’t visit him, media outlets reported a rift between the pair, overly exaggerating an already dramatic situation.

Even when Guardiola returned to see his beloved club face Manchester City earlier, the media speculated upon his motives, arguing that he was there to scout the club. TV replays of his reactions would suggest otherwise.

So while many expect Guardiola to return into the midst of his adorning fans, the fact is, his return to Barcelona may not be as welcoming as most think. One thing’s for sure, though, he has one immense mental and tactical battle on his hands.

Add Sportslens to your Google News Feed!