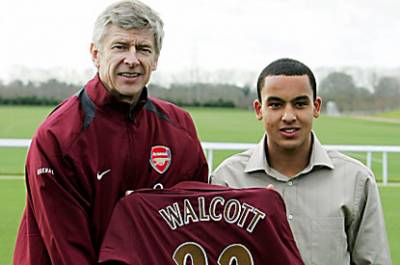

Ever since he signed for the club as a wide-eyed 16-year-old back in January of 2006, Arsenal prodigy Theo Walcott has been systematically lauded as the natural successor to Thierry Henry‘s considerable mantle at the club and, by proxy, unfairly derided for his continuing failure to do so.

Often seen as manager Arsene Wenger‘s youth-orientated folly personified, Walcott’s injury-strewn and inconsistent development attracted increasing criticism as the years wore on, as the ‘next big thing’ that the expectant English nation had promised themselves endured false start after false start – the yawning gap between his undoubted athleticism and his footballing nous often providing calamitous results.

However, now aged 21, Walcott is the exact same age that a certain Frenchman was when he joined Arsenal from Juventus in 1999.

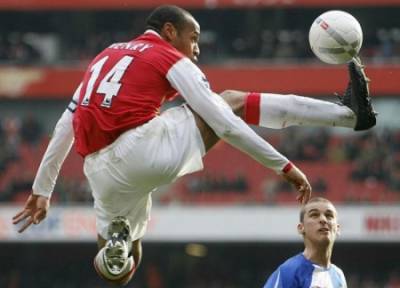

Henry was arguably entrenched in premature decline during his ill-fated time in Serie A, fading from view whilst posted out on the Old Lady’s right wing, watching his form dwindle almost as quickly as his previously burgeoning reputation.

Wenger then took a calculated gamble on the player which he had rated so highly as a 15-year-old at Monaco and the rest, as they say, is 226-goal Premier League history.

With Arsenal preparing for their Champions League game with Shakhtar Donetsk tonight, Wenger held his obligatory press conference to outline the depleted side that he plans to field against the Ukrainians – no Cesc Fabregas (hamstring), Alex Song (calf), Andrey Arshavin (virus) or Denilson (groin) – but, upon prompting, also felt the need to draw parallels between Walcott and the player that his young nonpareil has aped most throughout his career to date:

“Theo would love to play in the middle. Don’t forget that when Thierry Henry came here, he was a winger. When I played Henry as a central striker, he said to me: ‘But I can’t score goals.’

It’s difficult to compare the similarities – is Thierry a replica of Theo? Is Theo a replica of Thierry? No. But they have in common tremendous pace, they are good finishers and both are intelligent.”

Before making the move to a more central role, Henry was stationed on the flanks by Wenger thus training him to incisively cut inside from wider positions – a telling hallmark of his later play.

Given his four-year headstart on Henry, Wenger hinted that he believes Walcott may also be teetering on the verge of making the move into a move advanced position:

“[Walcott] is very close to playing that striker role. You know the two goals he scored against Newcastle [in the League Cup last week], they were typical of a striker who plays on a counter-attack.

But when I play with only one up front you like a guy who is good in the air sometimes, [for] when you kick it longer.

He can be prolific as once he is a yard in front of the defender, who can catch him? It looks to me that Theo has a calmness in front of goal. Before he rushed his decision, but now he is different.”

And with six well-taken goals in all competitions already this campaign, it’s hard to argue that particular strand of logic.

The emergence of what I’ll loosely refer to as the 4-2-3-1 formation in European football (think Barcelona, Real Madrid, Chelsea, Germany et al) has meant that the out-and-out striker is no longer playing such an influential role within any given side employing the tactic as was once the case – with the focus now being on the three floating trequartistas that usually play in support of a lone central forward.

The knock-on effect of this shift of influence is that the role of the central ‘target man’ role now requires a more refined and specific set of attributes than he ever has done previously. Deploying a lumpen giant with his elbows in everybody’s eye sockets or a flat-out, purposeless speed merchant just doesn’t cut it anymore.

In the 4-2-3-1, the striker is no longer relied upon for goals, but for holding up play, introducing others into attacking moves, pulling defenses around with tireless channel-furrowing and providing the main aerial focal point.

Walcott excels at curving runs from relatively wide positions in behind high defensive lines then basically tear-arsing toward goal at an unmatchable pace, leaving himself with plenty of time to decide what he intends to do once he gets there – a style of play which Wenger has struggled to nurture is far more suited to a supporting attacker rather than a wily (and spatially dynamic) centre forward.

Walcott has already come a long way in his current berth and, if I had any tangible say in the matter, I’d advise him to stay right (awful pun fully intended) where he is.

Add Sportslens to your Google News Feed!