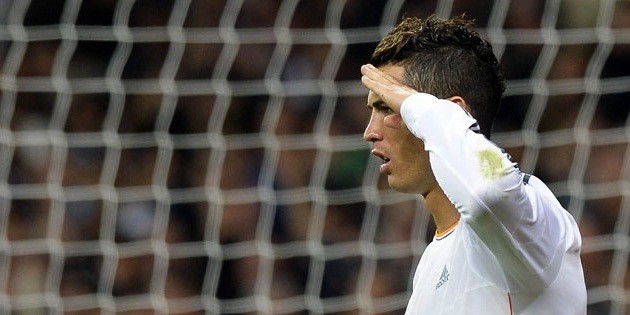

In the last week and a half, Cristiano Ronaldo has scored two absolute screamers against Osasuna, he has tallied two more against Champions League holders Bayern Munich, and he has single-handedly kept Madrid’s La Liga hopes alive by volley-stomping a ball into the back of the net with a move whose closest parallel is the act of kicking down a door.

Ronaldo has done all this, and what’s amazing is that it hasn’t seemed like an extraordinary week for him.

Ronaldo plays for Madrid, but he plays like Las Vegas. He is flashy, showy — and what he does with the ball is for many in the soccer world the greatest show on Earth. But in his Real Madrid years the the theatrics, the step-overs, the ball tricks more generally, have all been less frequent. It’s still a show, but the spectacle unfolds more slowly, and differently. Though when it does, it leaves fans wonderstruck and opposing teams devastated.

Here’s how it tends to play out these days:

Defenders will win the first few challenges. “We’re really bottling him up,” they’ll think. He’ll take a couple of ill-advised shots. “He’s having a bad game,” one fan will tell another.

Then it happens.

That innocuous pass he receives ten feet away from the penalty area, with his back to the goal, is suddenly in the back of the net. That inch of space that threatened to collapse in on him like a wave function turned out to be all the room he needed to launch. That’s how he wins. That’s how Vegas wins, too. First you fatten your wallet then you lose your bank account. First you lock him up then he punishes you. It’s the same phenomenon.

Above I likened his shot to a “launch.” As a metaphor, it’s more than apt. In fact, it’s just one of a family of propulsion metaphors that are commonly applied to Ronaldo.

Ronaldo was made to appropriate these metaphors. His game doesn’t merely suggest them, itinvokes them. Thinking to use them doesn’t require literary ingenuity on the part of the writer; they just fit. And the fit is natural and real and perfect.

When a metaphor is perfect it is because it can seem more descriptive than figurative. You forget it’s not literally true of the referent. It doesn’t cease being a metaphor, of course. But it just fits. Hand in glove. It fits like a hand in glove.

Our minds are representational engines, and the ease of representing Ronaldo’s shot as the launching of a projectile is evident to anyone who has seen him play. Plus, there are no jarring, ill-fitting details that remind us of the limitations of the metaphor. Kevin Durant may make it rain, but the fact that he makes it rain under a roof always calls to mind that it’s just a metaphor, after all. There’s no “of-course-he-doesn’t-literally-make-it-rain” interference with the Ronaldo metaphor.

Here are examples of the other propulsion metaphors I alluded to:

- “Ronaldo with an absolute rocket”

- “That shot was a missile”

- “Ronaldo with a torpedo into the back of the net.”

And while the following aren’t, strictly speaking, launches, they’re close enough to launches to be included in the family:

- “Ronaldo with a cannon of a shot.”

- “Ronaldo’s using all of his weapons there.”

These aren’t direct quotes, but they’re near enough actual words I’ve heard recently from commentators seeking to be descriptively effective without enlisting the splashy extravagance of Ray Hudson-style narration.

For its part, the propulsion metaphor is itself a species of another type of metaphor: the power orstrength metaphor.

Here are some power/strength metaphors not of the propulsion kind:

- “Ronaldo with a towering header.”

- “Ronaldo with a thunderbolt.”

Here I must introduce — and really who can forget? — Sepp Blatter’s contribution to this enterprise. Blatter, who is the current president of FIFA, mock-strutted on stage, that is, in front of an audience, to make fun of Ronaldo. To Blatter, Ronaldo is a peacockish commander whose mannerisms are exaggerated and whose mirror-gazing is infinite. Ronaldo’s payback? A military strike of a goal, with an ensuing salute so delicious it made you forget that the dispute is between an all-time great and a soccer bureaucrat who has all-time age.

Still, it wounded Ronaldo to be made fun of by the FIFA chief. It wounded him because he really is one of the game’s best ever players, and rather than celebrate his abilities Blatter chose to ridicule Ronaldo’s proclivities. More on this aspect of Ronaldo in a moment.

First, let’s consider what the above superlatives, all taken together, suggest of Ronaldo. His game appropriates the entire gamut of strength metaphors. They are his to proudly display. But Ronaldo is even more impressive than that, for that’s not the only metaphor family that Ronaldo has a claim on.

There is an entirely different kind of metaphor sometimes used of other players: the finessemetaphor.

- “He’s a wizard on the ball”

- “He’s got the ball glued to his feet”

- “What a silky-smooth pass!”

Though metaphors of this kind might aptly describe Ronaldo’s game in certain instances, the right fit is usually the strength metaphor. Yes, his ability on the ball requires finesse metaphors on many occasions. But consider his performance in the recent “winner-gets-in” international match between Portugal and Sweden.

There was nothing magical about Ronaldo’s dissection of Sweden. In that game (as in most games these days), he was not a wizard but a machine. Coldly efficient and unforgiving — underneath the shiny exterior lies an even shinier, metallic interior.

When his two one-on-ones against the Swedish keeper ended with the ball in the back of the net, it wasn’t because he had done anything magical. These weren’t goals of divine inspiration or sublime inventiveness. Though they covered the same distance on the field, these weren’t Maradona against England, or Messi against Getafe.

Ronaldo’s goals were goals borne of perfect execution. 90 out 100 players find a way to botch at least one of those two chances. And the 9 out of the 10 that are left actually surprise us when they get one of the two chances right.

The one whose success doesn’t surprise us is Ronaldo — we expect to see exactly what we saw in that match. We expect the machine to work as it’s supposed to. The input is given (Ronaldo breakaway) and the output is assured (Ronaldo goal).

Much is made of the all-around player. One way to test whether a given player is an all-around talent is to see if different kinds of metaphors can successfully apply to him. Though I’ve adduced evidence for Ronaldo’s status as the strength metaphor standard bearer, he’s clearly creative enough on the ball to warrant his share of the finesse or skill metaphors, too.

To round out his image — because, let’s face it, some of what makes Ronaldo so fascinating is unrelated to his game — let’s expand our view to include his non-soccer features.

Ronaldo’s beautiful. He’s not handsome. He’s beautiful. That’s a half-compliment, since men are supposed to be handsome rather than beautiful. But he plays like a runway model, each stride revealing the latest collection. In fact he’s too glitzy. His tan, when it’s not too orange, carries the transcendent glow of McDonald’s arches at sunset.

His is a kind of cheap glamour, or would be, anyway, if it wasn’t for the fact that affording his brand of cheap glamour even for a week would require many of us to refinance our homes. His hair styles have gone through several different incarnations (the ramen noodle look being the absolute low point), each showcasing a meticulous devotion to flashiness.

The moment he acquires a trophy two things dawn on Ronaldo: (1) he is (in that moment but to him probably in all moments) the best player in the world and (2) he looks really, really good. The first comes to mind when he looks at the trophy, the second when he looks through the trophy. Or, rather, when the trophy’s shiny metal provides a makeshift mirror for Ronaldo to judge how his hair has held up against the rigors of his performance. The result must always be: and Ronaldo saw that it was good.

His free-kick stance is the stuff of Michelangelo. And once his free kick smashes into the net, he embarks on goal celebrations that are, at the very least, intensely self-congratulatory. What’s funny is that you get the impression that while to us they seem over the top, to him they are understated. They showcase his restraint.

But painting him as a modern day Narcissus is not fair. His self-enchantment is not debilitating, but catalytic to his success. Narcissus is spell-bound by his beauty and it steers him off his path. Ronaldo is energized by his endowments. Who can forget the reasons Ronaldo provided for why he receives so much hate: “I’m good at soccer, rich, and good-looking.”

When LeBron James was at a particularly low point after the Miami Heat lost in the 2011 NBA Finals, he publicly comforted himself by comparing his life to the lives of his detractors. The argument was: his life, even sans an NBA title, is surpassingly greater than the lives of the people who watch his games. It wasn’t meant to explain why he gets hate, but to put the hate in context. Compared to the everyday person, LeBron’s life is charmed. No, it’s more than that. It’s enchanted.

But Ronaldo went further in that he gave the rationale behind the hate. It is jealousy. It is envy. Ronaldo has the whole package, his detractors have perhaps none of those three qualities; at most they possess one. And so they hate. Because he has all three. Because he is a dragon on the pitch and a prince off it, and the pot of gold is his as well. He’s smug, yes, but he’s also Smaug.

The only thorn in his side is a certain hobbit-sized rival; but at the moment Ronaldo seems to be reversing the plot. I for one can’t wait to see what happens at the World Cup.

Add Sportslens to your Google News Feed!